David Cronenberg: Transformation: Candice Breitz, James Coupe, Marcel Dzama, Jeremy Shaw, Jamie Shovlin, Laurel Woodcock

Through Dec 29, 2013

Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA), organized by MOCCA and the Toronto International Film Festival

What’s on view: Six artists were given the task of creating art inspired by the distinctive Canadian film director

Corinna Kirsch: I was surprised that so many of the works that were asked to “respond” to Cronenberg ended up borrowing from the director’s films: Candace Breitz used footage from The Brood; Laurel Woodcock adhered vinyl lettering with words from Cronenberg’s films; and Marcel Dzama paid homage Cronenberg’s most memorable scenes—the ones that get scratched into your brain like the monstrous births, forced TV watching, and heads exploding—by showing similar events in his own film, A Jester’s Dance. Maybe that’s a sign of distinction. Cronenberg’s films are too one-of-a-kind; you can’t be Cronenberg-like without seeming derivative.

I wonder, could there be no such thing as a painting that’s Cronenberg-like? (In this exhibition, the response is the sound of crickets.)

There were a few works that weren’t derivative. James Coupe’s Swarm, an installation of 16 flatscreen monitors lined up overhead into a square shape, held up by a series of poles. A wall-label noted you’d be filmed, too. The monitors showed what looked like an earlier crowd of people gathered at MOCCA, and as you walked around the square, the crowds changed. Some of the monitors were empty, but you never saw yourself. I assume we were being recorded as raw footage for later visitors, but I don’t know. After all, how functional can surveillance be if the watchers’ purposes are known? Anyway, maybe I’m setting the bar low here, but I was pleased this work wasn’t plastered all-over with “Cronenberg.”

Paddy: Given the perameters of the show I’m not sure it’s fair to call the work derivative, though we can certainly say that the approach didn’t yield the results one might hope for given the “assignment” feel to the show. Honestly, I think it’s hard to evoke the terror Cronenberg produces in a movie theatre designed for 90-minutes-plus of movie watching in a gallery space designed for much shorter term viewing and transformative experience. They are almost inherently safe places.

With Coupe, I rather liked that the motion detector that flicked your image off the screen and onto another wasn’t hidden. It was attached to the pole of TVs and a light went off whenever it recognized a body. I read that as a message about surveillance—it doesn’t have to bother hiding—and I guess that’s the case, because apparently the piece uses social media algorithms to group visitors. Presumably, at some point, we too are integrated into these groups on the screen.

What it tells us about social media is a little murky, imo, because it’s not using any of the information that makes media social; it doesn’t know my friends, my interests, my buying behavior and I wouldn’t freely offer it if asked. So what exactly is it evaluating to make these groups? And what is it telling me about how it functions? I wish it were more.

Corinna: You’re right; if it tells us anything about social media, it’s that we don’t know how we’re being “used” by it.

Paddy: Overall, Jeremy Shaw’s video, “Introduction to The Memory Personality” had the most to say and oddly enough, it was the easiest to miss in its location beside the front desk, and outside the exhibition. “It doesn’t matter what you forget. Your subconscious will remember what your conscious mind will remember it has forgotten,” says a voice over a hallway before a flash of black interupts the viewed image. *Blink*. The hall image shifts slightly. *Blink* The voice now talks over a sunset. *Blink* The image erodes, *Blink* and erodes.

I wrote all this down, as I watched it, assuming both my subconscious and conscious mind would forget the video (I’m afflicted with a terrible memory…or am I???).

Corinna: Nope. I did the same, and wrote down most of what the narrator said. Maybe it has to do with how all that repetition evokes rote, secondary-school memorization? But of course that saying “It doesn’t matter what you forget. Your subconscious will remember what your conscious mind will remember it has forgotten” made me feel a little better about my futility.

Paddy: More than that ominous voice, though, we then see a collage of spooky images, a data stream the resembles the matrix, epilepsy evoking image changes, a CD and a deep voice styled from the 90’s saying “Remember dancing? Remember not sleeping? and time becomes a loop…”

It felt like I was living an episode of the X-Files, and was willing to participate in the idea that my mind might get hijacked.

Let your conscious mind stay relaxed.

Do your past failures still bother you?

Does life seem vague and unreal to you?

You are aware of everything.

No need for awareness.

By the time the piece was through, I was wanting my mind hijacked. There was a very Matrix moment in the film, except you chose the reprogramming pill rather than awareness. In 2013, somehow that seemed like a good option.

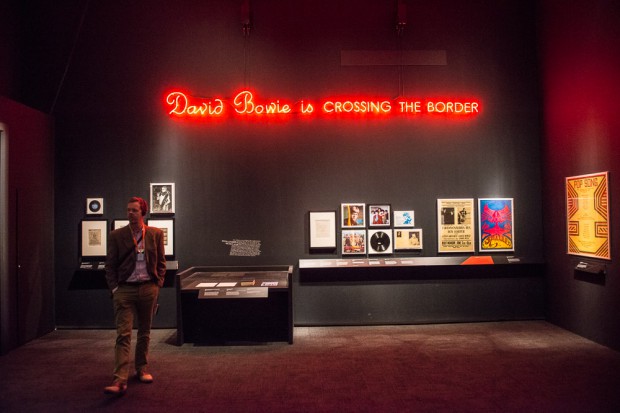

David Bowie is

Through November 27, 2013

The Art Gallery of Ontario

What’s on view: A chronological audio-guide takes you through David Bowie’s life, as seen through his clothes, video recordings, knick-knacks, posters, books, lyric sheets, and theatrical sets

Paddy: Let’s begin with the obvious: This is a terrible show. Whereas the Cronenberg show constructed influence where it could have simply sought it out, David Bowie is, would have viewers believe the entire 70’s music scene occurred thanks to Bowie singular genius. The entire show, which takes up two floors, has the feel of record label promotion. I actually had to check to make sure there wasn’t a sponsor of that nature.

Corinna: I wasn’t excited about seeing the show, other than to find out what it was about; the Victoria & Albert Museum has somehow got the lockdown on releasing photos of the installation. To draw in the crowds, I suppose.

Paddy: And that worked. We had to get advanced tickets and they were sold out for most of the day (which was a Saturday).

Corinna: Now I want to be fun and all, and like not-art exhibitions, but this was, as you mentioned, just a bad show. From the start, you’re given an audio guide to wear through the exhibition, which jumps from playing snippets of Bowie songs to factoids about his life. When you enter the exhibition, the first thing you see is a mannequin wearing a Bowie costume. I thought maybe it’d be a fashion show, but there was no focus as each room you walk into had a completely different set of ideas informing it—and only few focused on a single idea.

Paddy: I hadn’t noticed that, I guess because the exhibition began with some semblance of structure before it completely unraveled, but you’re right. Even the start of the exhibition, which begins with his early life is pretty bewildering. Try reading a plaque, looking at written ephemera and listening to an audio guide all at the same time. Mostly I got that he was making music as a high school student, and that if he hadn’t been musically inclined he would have been a writer (that was a quote on the wall). Reading Bowie’s Wikipedia page, it seems most of the factoids in this exhibition are also online.

From there, we went to the Space Oddity room, which I liked mostly because the audio tour component was just song and it’s really great. The song is about an ill-fated fictional astronaut named Major Tom, with a title alluding to Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey, a film released a year prior, in 1968.

Basically, though, the gallery is just a collection of ephemera and factoids, with little to no reflection offered. Take, for example, the Victor Vasarely cover for the single, which was used because a Mercury Records exec collected the artist. It’s a great demonstration of how individuals and relationships shape culture, but the curators squander the window this cover provides. A bit of adjacent wall text blindly interprets the BBC’s unusual decision to use the macabre song during its coverage of the Apollo 11 landing as proof of its power. Where was the statement from the individual who made the decision in the first place?

Corinna: The worst room of all was the “showroom” upstairs, plastered with mannequins, videos, lyric sheets, album art, art “related” to Bowie, and posters. It’s like someone’s notes for an exhibition exploded, and worst of all, I couldn’t find out anything about Bowie, personally. Well, except for the fact that Bowie mannequins stood atop larger-than-life books that he was presumably influenced by. So he became more influential than those books themselves?

Paddy: Yeah, that was remarkably stupid, and it took away from the video of Bowie’s 1979 Saturday Night Live performance of “The Man Who Sold the World”, which is really incredible. Bowie in a fat suit, unable to move. You can clearly see his influence on David Lynch here – I’m thinking specifically of the costumes in Dune.

Botched as this room is, it did also hold some of the works that did the most to reveal his process; the video of a designer explaining how easy Bowie made everything look. “10 hours in the studio and you’d come out with something great!” he exclaimed. Then you see the written lyrics of “Fashion,” which have only one revision. The chorus “like hell up ahead, burn and play” is replaced with “fashion”.

And yet, this was also where the exhibition really fell apart for me. We’re told the 60’s are about authenticity, but Bowie, at the age of 20 (1967) likes acting, playing, masks and make up. If you believed the text in this exhibition, he single-handedly lead a sea-change. There’s no mention of Queen, The Psychedelic Furs, Iggy Pop, as other leaders, which is a little ridiculous. “He looked like nothing that had come before,” Gary Kemp tells us, noting that he had short hair. Kemp, like the show’s curators though, doesn’t attempt to cite contemporaries, so what you end up with is a construction of individual genius. Obviously Bowie is gifted, but the narrative that he constructed the 70s on his own is not only inaccurate, but fails to match Bowie’s own process, which is often collaborative.

By the end of the exhibition, this nonsense reaches a pinnacle. We’re in a large room, the walls filled with projections of Bowie performing live. On a column, a bit of text made a small part of my soul die. “Bowie is a radically innovative live performer. In one thousand live dates in 31 countries during 12 international tours between 1972 and 2004, he has fused rock music with performance techniques from mine to street dance.” That bit of corporate press release language comes straight from the music industry to the AGO, and it does absolutely nothing to contextualize Bowie’s place in culture. I left enraged.

Comments on this entry are closed.