WK: So did people get frustrated in that process? Was everything based on total consensus?

AM: Well, we had meetings every week. And we had a big table that was in the room. We were sitting there for an hour or two hours, depending on who showed up. If you had a project to pitch, you’d come and pitch it, [usually to] Bobby and Becky [Howland] and I, who were basically running the place. And if other people came to the meeting, they would be part of that process, to decide whether it was a good idea or not. We pretty much took every proposal that came our way. People walked in and pitched their show, and they did it a couple months later. There never was a stack-up, really. It was just a magic kind of thing. It all worked. There are many reasons why it shouldn’t have worked, but it did.

WK: So people were prepared to sit there for a really long time and talk things out, or did you have an intuitive process?

AM: Well, this is a difference between artists’ process in consensus and political process in consensus. I think people with a political point of view hold it. You can talk to me until you’re blue in the face about monetarism and stakeholders and all that kind of crap-ass entrepreneurial talk, and I won’t buy it. But if you have an art idea and I have an art idea, and your idea’s obviously better than mine, I’m gonna roll over. That’s part of the nature of collective process among artists; if somebody had an idea, we could critique it constructively and give-and-take in a way that’s just not possible in political discussion.

In Colab, the big general meetings where there were competing factions, those could be pretty brutal because money was at stake. People had to argue their project’s superiority over other projects to get the votes, to get the cash. So those could be nasty. But to run the space ABC No Rio, it was always easy for us.

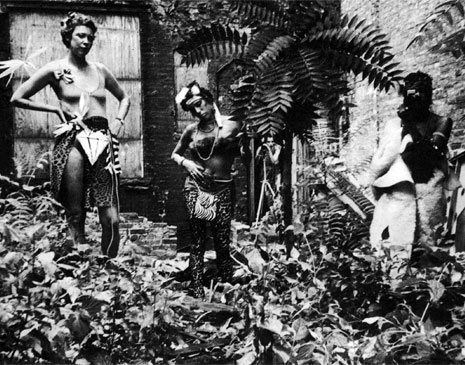

Cave girls in No Rio's backyard. From left, Becky Howland, Judy Ross, Kiki Smith and Marnie Greenholz. (Photo by Teri Slotkin, photo courtesy of "ABC No Rio Dinero")

WK: So what was the mainstream art world’s view of the whole project, of ABC No Rio and Colab?

AM: Well, honestly, I can’t really say what the mainstream art world was thinking about ABC No Rio and Colab, except insofar as the “Times Square Show” happened in June of ‘80. And the gallerists raided the place. They were invited, of course, and they picked up a whole bunch of people for gallery careers. So the organization was suddenly denuded of its most productive and active members. I think Walter Robinson called it a “farm team for the big leagues.”

So I think that was the reaction of the mainstream art world. And then Diego Cortez produced “New York New Wave” in 1981 at P.S.1, which sort of fused the music and popular culture thing together with art and made a career of Keith Haring, Jean Michel Basquiat, and a bunch of other people. Robert Mapplethorpe was in that show as well. And after that, it was over.

WK: Because they’d found their poster children for the era?

AM: Exactly. They’d found their people. When you’re in the thick of it, riding the culture wave in New York, it’s pretty short. So that was the end of Colab, really. People were no longer interested. I mean, of course that’s not true, but in terms of a strong relation to the mainstream commercial art world, it was over. After ‘81.

WK: Was there an official handing it over to Jack [Waters] and Peter [Cramer] [of ABC No Rio’s following “Decadent Era”]?

AM: Yep.

WK: So how was that decision made?

AM: Basically, Becky [Howland] wanted to make her own art, Bobby [Robert Goldman] got an apartment and moved out, so it was just me. And there weren’t so many people interested to do shows. This is all in the book, but Jack and Peter had just produced a big show called “The Seven Days of Creation,” where they basically lived in the space for a week with their theater group. It was only natural. Plus, they didn’t have a place to live, and Bobby had just moved out of the basement. It’s terribly uncomfortable if you’ve been in there, it’s damp and miserable. But, you know, it was free! So it’s hard to argue with if you don’t have a place to live. So they were happy to do it, and they did it for a long time, even after they had an apartment.

WK: Were there any instances where the city just came in and tried to throw you guys out?

AM: They made many efforts. They basically would run up and post legal notices, people would try and intimidate us, all sorts of stuff. And Bobby dealt with most of this because he lived there, but like I said, he was a really in-your-face guy. Also, he and I are both from California, and we both went to University of California during the period when Ronald Reagan was trying to discipline it, so we both had a lot of political experience. So you just kind of become savvy.

Also the city had, like, ten thousand buildings to manage, and I don’t think I’m exaggerating. An internal monologue you alway play in the back of your mind: (I’m playing the city bureaucrat now) I’m gonna get those fuckers outta there! I hate those guys! Let’s get them out, send somebody down there to distress them! But then comes a boiler explosion in the Bronx. Three people burned! No heat, the temperature’s ten degrees! Well, you still hate those motherfuckers down at ABC No Rio, but you can’t do anything about it. [Laughs]

Our problem was the people in property management. They hated us, always did. You just wait til those guys retire, and actually, they did. And they’ve always got bigger problems. The great thing was that Jack’s mother was a city bureaucrat in Baltimore. If you talk to him, he talks reeeeallly slooooow. Reeeaallly caree-fuulllyy. So every time something would go wrong, he would file a report with the cops or the fire department, accusing the city of mismanagement. So the city would come and say “We’re gonna evict you, we’re gonna do process against you,” and Jack would say, “Well, okay.” in his ambling way. “We’re gonna present our dossier showing your feckless management over the last number of years. I have here thirty-four citations from this year alone.” So basically if the city ever took ABC to court in an eviction proceeding, Jack and Peter could demonstrate that they were far more responsible managers than the city could hope to be. It was a clear case and they had an immense dossier to prove it.

WK: That’s smart.

AM: Yea, I think that’s the reason it’s still there. I wouldn’t have the energy or the aptitude or patience for that kind of thing. Everybody kind of brought to the place the particular special skills that they had, and Steven Englander, what he’s done with the fundraising and the city, this intensive purposeful-ness…I couldn’t imagine. I can’t even do that for myself. It’s amazing. So when ABC needed particular skills and particular people, they showed up. It’s really always been a tremendous fortune for the place.

WK: Do you think that’s kind of why history hasn’t forgotten about it, whereas something like Fashion Moda isn’t as well-known? Partly because there is still a physical structure there, but also because people just took really good care of it, and fought that hard for it?

AM: It was always a collective. It always had a very strong political dimension. And it was always culture…so it had feet in all the right places. Or, you know, tentacles in all the right places. Plus, Marc Miller and I made a book in 1985 that really was an important document, not only for ABC No Rio, but for a bunch of other groups. Marc was a professional historian, PHD at the time. I was trained as a historian and journalist, and now I’m also a professional historian. So, you know, we did not neglect to maintain the profile.

René Ricard’s essay “The Radiant Child” inspired us to write that book. He basically said “Forget about everybody else in the East Village, the only people who matter are Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.The rest of it’s just garbage.” And we were like, Excuse me?? Yea, well, we’d better get busy because this asshole’s gonna write our history for us, and we’re not in it. So for me, that was really inspiring. A negative inspiration. [Laughs] I tell artists this all the time: You have to do your history. If you don’t, you’ll be forgotten.

{ 4 comments }

Very nice interview, Alan. Looking forward to the others in the series.

Hello Whitney,

Please list photo credit on my photo of Alan as:

©1980 Becky Howland. All rights reserved.

Thank you!

Hey Becky,

Thanks for commenting; I added the proper credit to both photos. Sorry we didn’t get it right the first time! (And great work, by the way)

Will

Thanks for catching that- sorry!

Comments on this entry are closed.