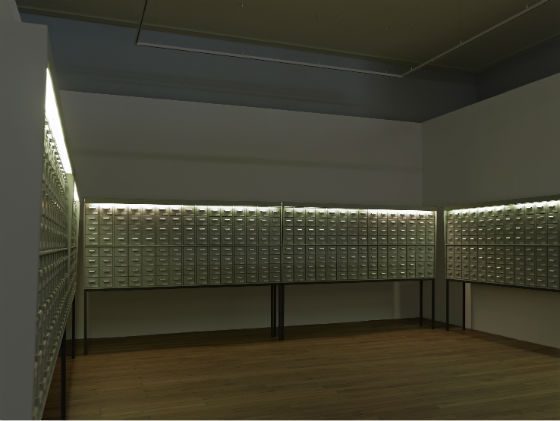

Wesley Meuris, Compare Two Magnificent Pieces of the Collection (2012), Installation. Photo Copyright Eric Chenal.

Wesley Meuris

R-05.Q-IP.0001

Casino Luxembourg

May 12 – September 2, 2012

The reception desk at Casino Luxembourg is spotless. Fliers are conspicuously absent. The display rack is empty.

I ask where Wesley Meuris’s exhibition begins, and two docents confer. There’s disagreement over where the exhibition ends, and one replies, “Well, you’re already in the exhibition.”

Of course. The reception desk is a Wesley Meuris piece. Indeed, the entire reception area, including potted palms, is a work by Meuris. The space is at once familiar and disconcerting in its indifference.

Belgian artist Wesley Meuris is preoccupied with the relationship between the built environment and human behavior, and his solo exhibition R-05.Q-IP.0001, at the Casino Luxembourg through September 2, focuses on the ways in which museums stage encounters with objects. With architectural drawings and diagrams as well as objects and installations, the exhibition examines a range of museum practices, including classifying, archiving, and marketing.

On the first floor, works address those elements that are “outside” an exhibition proper. Hanging on the wall is a series of admission tickets to fictional shows, such as “Mythic Creatures,” “Homeland & Landscape,” and “Biennale of Contemporary Art – The Coal Mine Venue.” (The latter bears a remarkable resemblance to this year’s Manifesta, a European biennale taking place in a former mine in Genk, Belgium.) Also on display are promotional posters. A poster for a fictional natural history exhibition advertises SEX AT THE MUSEUM and blurbs “You’ll be amazed at what nature gets up to. Come and discover its bizarre and intimate secrets.” Another poster appeals to the values of novelty and tourism with its pitch for an arts festival in Antarctica where viewers can “visit art installations in an open-air exhibition at minus 30˚ C.” Both Admission Tickets (2012) and Project Advertisements (2012) are uncanny reproductions of the visual style and rhetoric of promotional materials now used by museums to attract viewers.

Shuttle service will be available during the show (2012) is a bus shelter. An oak bench with ceramic tile frame and display cases on front and back, it is a waiting area that also functions as ad space. The piece evokes the ubiquity of display, and the circumference of exhibitions that begin well before one enters a museum. The bus shelter—inside this exhibition—stands alone in a room lit only by the light boxes in each display case. The work is placed in the center of the room and I automatically walk around the shelter as if it were sculpture. I walk around the piece many times, and I become aware that my circling—dutiful, artificial—is itself an art-world performance.

Shuttle service will be available during the show recalls the artist’s previous works that explore architectural form, such as his 2004 renovation of an abandoned swimming pool in Willebroek, Belgium, and his 2005 construction of 17 changing room cubicles (like those at a swimming pool) in a building on the Catholic University Kortijk campus. Most recently, Meuris has constructed habitable enclosures for specific animals, such as the Arctic fox, the okapi, and the Bolivian squirrel monkey. The empty cages evoke stage sets and redirect attention to the theater of captivity. As Meuris states in a text posted on his website, “But more important still in the construction of such cages, is the comfort that we (viewers) generally experience when we look at animals in captivity, most often in zoos.”

Wesley Meuris, The World's Most Important Artists (2009-2012), Installation. Photograph copyright Eric Chenal.

The most compelling section of R-05.Q-IP.0001 takes place on the Casino’s second floor. At the top of the stairs, a white cube features Vision Restored (2012), a freestanding object with the profile of a display cabinet but solid and painted blue. Situated in the center of the space, the work asserts the autonomy of sculpture despite the oddity of a railing at its base and a display light around the perimeter of its upper end. Circling the object (as its placement demands), one finds that the back of the object is a display case, lit but empty. The presumed autonomy of this “sculpture” is exposed as a functional—but empty—vitrine. In moving into the white cube, the viewer passes from an encounter with the display of form to an encounter with the form of display.

Many works in the exhibition, including Vision Restored, were conceived specifically with the Casino in mind. Built in 1882, the Casino Luxembourg was not only a casino but a cultural center that hosted concerts, dances, and lectures. The Casino was converted into an exhibition space in the mid-1990s, and open-topped cubes were placed within the ornate rooms. Floral motifs, the dainty figures of a wall mural, or geometric patterns peek above the exhibition cubes, a reminder of all that the modernist white cube was supposed to suppress.

The Casino provides an interesting context for Meuris’s staging of display situations. One of the most striking situations is Compare two magnificent pieces of the collection (2012). Meuris painted the cube inside and out with a dark red. A single light highlights a wall panel cordoned by a low railing. Entering the dim room with its dark walls, I am keyed—viscerally—to peering at light-sensitive Old Master paintings. Meuris is quite effective at staging display situations that elicit automatic and visceral expectations. It is only at the moment of frustration—(nothing to see!)—that my expectations are recognized as indeed “automatic” and I am compelled to redirect my attention to what is typically at the periphery of museum experience.

Leaving the red cube, I pass a long vitrine titled Story of a Unique Exhibition (2012). The vitrine is empty but for information boards specifying “document,” “image,” or “object.” The irony of the adjective “unique” is that an imagined argument for “uniqueness” is developed through generic components.

Wesley Meuris, Display Kit for Portrait Statues—40 Meaningful Curators of Contemporary Art (2012), Installation. Photograph copyright Eric Chenal.

Story of a Unique Exhibition leads to the Casino’s former dance hall where the artist has erected large metal frames that support rows of small pedestals. The modular units—a grid of forty plinths—are a reminder that repetition serves the taxonomic impulse. The work’s title, Display Kit for Portrait Statues –40 Meaningful Curators of Contemporary Art, pokes fun of the art curator “star,” the phenomenon reduced to a storeroom’s shelving system.

While I’m all for poking fun of the art world, I find the mocking tone of this title, and other titles, distracting. Especially irritating is the ironic redundancy of adjectives such as “meaningful” and “magnificent.” For an artist who has so masterfully re-presented museum-speak in series such as Admission Tickets and Advertisement Posters, this ironic posturing is overkill. We get it. It is the very earnestness and subtlety of Meuris’s analysis of display practices that invites critical reflection.

The artist’s publication FEAK – Foundation for Exhibiting Art and Knowledge (ABL Publishers and Cultuurcentrum Brugge in collaboration with Casino Luxembourg) accompanies the exhibition. FEAK is a fictional global entity that conceives, organizes, archives, tours, and promotes exhibitions—a one-stop shop for all exhibition needs. The book purports to document FEAK’s many activities. These documents are, in effect, the artist’s investigations of art world rhetoric and practices. (My favorite is a set of diagrams for how touring exhibitions are to be packed into shipping containers.)

One of FEAK’s activities is generating an exhibition taxonomy. R-05.Q-IP.0001, the title of Meuris’s show, is its classification: R-05 = research; Q-IP = art platform; 0001 = unique exhibition number. R-05.Q-IP.0001 includes many drawings and diagrams, ostensibly produced under the umbrella of FEAK. These include architectural drawings for fictional displays, such as An Outstanding Sculpture Garden (2012), and The Most Inspiring Fair of the World (2012). Ink and watercolor charts depict spatial arrangements of exhibitions available for loan through FEAK, including Machines that Changed the World (2012) and Drawing – A Survey Through Time (2012).

Peering at the floor plans of fictional exhibition halls, the complex geometries of archives, and diagrams of make-believe, but plausible, data, I am suspended in a meticulously recorded system. Meuris’s works on paper are impressive in their commanding mastery of the multiple discourses that make up museology, but ultimately they feel like academic exercises. In contrast, the artist’s objects and installations are immediately and viscerally engaging. Works such as Vision Restored and Compare two magnificent pieces of the collection draw me through the space: I am poised to look—and then that poise is challenged. Self-conscious, I ask how it is that I am here, staring into an empty vitrine or circling an absence.

Comments on this entry are closed.