“Progressive.” “Groundbreaking.” “Pioneer.”

Such praise feels a little superficial when applied to Sanja Iveković, whose forty-year retrospective demands we look not forward, but back, and around; inside MoMA are works which actively direct our attention under the cultural rug. The artist herself is little-known in the United States, but described as a European cult figure. “You cannot compare her with Jeff Koons or even Marina Abramović,” remarks Enrico Lunghi, the director of the Mudam in Luxembourg, “She is not a popular artist. You cannot just look at her work, you have to go deep into it.”

The keystone of the exhibition, and perhaps the work for which Iveković is best known, is Lady Rosa of Luxembourg: a 69-foot-tall obelisk in the second-floor atrium, crowned with a gilded pregnant Nike. She holds out a wreath at arms-length, poised as though looking down over a cliff, her sheer robes billowing behind her. Repeated lines of text wrap around the monument’s square base:

LA RÉSISTANCE, LA JUSTICE, LA LIBERTÉ, L’INDÉPENDANCE

KITSCH, KULTUR, KAPITAL, KUNST

and

WHORE, BITCH, MADONNA, VIRGIN.

Wall text informs viewers that Lady Rosa is a pregnant version of Gëlle Fra, a Luxembourg monument commemorating male heroism of volunteers who fought in World War I. Iveković’s adaptation honors Rosa Luxemburg, a Marxist philosopher and activist who was executed for her political ideas in 1919.

Local TV news reports, which are displayed amongst multi-lingual newspapers, magazines, and reactionary cartoons, are a highlight; the statue’s 2001 installation sparked an international polemic, particularly infuriating those who lived through World War II. One extremely pissed-off old woman seethes at the pedestal: “How dare they write kitsch, kitsch, kitsch on a monument celebrating the heroes who fought for the fatherland! It’s scandalous! It’s scandal!” Another, elderly man declares, “No democratic country in the world would have allowed ”¦ a statue with such inscriptions.” This sounds old-fashioned, but he might be right. A younger, local artist is more sedate: “the pedestal is more of a problem itself than the fact that women and children are beaten on a daily basis,” he reflects.

Photo from a 2009 installation, "Turkish Report," from the 11th Istanbul Biennial. (Photo courtesy of MoMA.)

Just as much of the public was reluctant to deal with Lady Rosa’s ugly subtext, viewers at MoMA tend to overlook what resemble blood-covered tissues, littered throughout the exhibition. While most visitors avoid touching these– you’ll overhear speculation about whether we’re allowed to– the red fliers’ text informs us that the United States is one of eight countries which has yet to ratify CEDAW, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Squatting on MoMA’s floor to uncrumple the paper, one actively restores a piece of overlooked information– more importantly, witness every one else ignoring it. The discovery triggers an automatic need tell some one. Throwing out the bill, at our feet, seems far more effective than losing it to the white wall; one hangs, forgettably, at the very end of the exhibition.

Sanja Iveković is by now well-versed in campaign tactics, amidst a volatile political climate. She was born in Zagreb in 1949 and spent her formative years in post-1968 Yugoslavia: “1968” referring to the Croatian Spring, a civil rights movement which focused heavily on freedom to express nationalist pride. During WWII, the Independent State of Croatia had been a puppet state for Nazi Germany; over the course of Iveković’s lifetime, Yugoslavia has been subject to unilateral Communist rule, economic emergency, wars, silent ethnic cleansing, and subsequent sexual and physical atrocities committed against women.

Carol Kino of the Times dubs her the “anti-Abramović.” While both women came of age around the same time in Yugoslavia, and both were aligned with Yugoslavia’s New Art Practice, Iveković stayed in Croatia and made her career entirely outside of the commercial system. She has formed several NGOS and played a key role in Zagreb’s Centre for Women’s Studies, an organization which promotes publication and research of women’s issues. Sanja Iveković is reportedly the first Croatian to declare herself a feminist artist.

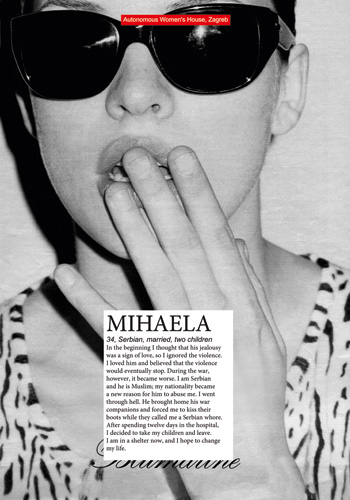

One of several large-scale inkjet prints in "Women's House (Sunglasses)" 2002- present. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.)

To the American eye, the rest of the exhibition recalls much of the Western feminist conceptual art of Iveković’s generation; unlike the school of Barbara Kruger, Martha Wilson, and Hannah Wilke, though, Iveković increasingly pinpoints specific historical events. Her black-and-white photographs, video, and magazine collages, with sparse text-and-image pairings, are characterized by the New Art Practice’s affinity for publication-as-art.

Close-ups of models in fashion ads for sunglasses, the 2004 inkjet prints Women’s House (Sunglasses), line the third floor entry hall, each bearing a small red bar with the name of a women’s shelter and a first-person account of sexual violence or medical injustices. An abbreviated caption renders a woman at the mercy of her longtime doctor:

AGNIESZKA

28, Polish, married, three children

All my pregnancies were supervised by the same woman doctor ”¦ For eight months in my last pregnancy she allowed me to believe that I was carrying a healthy child ”¦ It turned out that my child had severe developmental disabilities ”¦ Rozalka was born with no limbs.

Though a presentation of women’s tragedies as fashion spreads has little capacity to shock the contemporary viewer — there’s a sense throughout of how-many-times-do-I-have-to-tell-you-nicely-before-we-erect-another-giant-fucking-monument — Iveković claims in a 2009 interview that violence against women was, unfathomably, still a “hidden issue” in her country in the mid-nineties.

While educational posters speak to immediate social issues in 2000s Croatia, it’s decades-long commitment to women’s rights that speaks today at MoMA. The artist claims that she wanted to “reintroduce real women from our society … into public discourse.” Often, she does this by burying them: photos of real women are paired with similarly-posed glamour shots; magazine models are scratched, punctured, sliced, and torn; a grid of black-and-white photos are penned with phrases like “A life full of suffering” and “Bored of the good girl role.”

Triangle. 1979. Performance, 18 min.: Four gelatin silver prints with printed text, each print: 12 x 15 7/8" (30.5 x 40.4 cm). (screenshot from the Museum of Modern Art, cropped without text).

Iveković, too, gets bored of the good girl role; through performance, she is occasionally free to shed the informative, but obligatory, tone. In one of her best-known performances, Triangle (1979), Iveković feigns public masturbation as civil disobedience during a visit from President Tito. One photograph documents Iveković lounging on her balcony, which was forbidden; to the left, a verticle stack of three views of Tito’s car and watchful police, who reportedly show up at her door within 18 minutes. Now, it’s not much more than a long-faded imprint, but this is the potential of documentation: we are asked to do the tedious but necessary work of conceiving of the reality of a dictatorship.

While all of these together achieve a sort of manifesto, the most peculiar work communicates on a more emotional level. In Resnik, a 1994 installation at the end of the exhibition, an aerial video of a panning, black-and-white landscape is projected on the back wall of a dark room filled with various people-sized (now withering) tropical plants. Every ten seconds or so, the screen goes black, and a solitary dripping sound signals the appearance of a word, on a random part of the wall; part of a sample series:

LEFT REPLACE BUY NEW BEHIND FUTURE DROP HOPE

According to the wall text, Resnik,which refers to a refugee camp near Zagreb, is meant to replicate the experience of a refugee, rather than the constructed exclusionary historical narrative in which the rest of us can find a place. While the rest of the works in the exhibition speak to the outside world about the victim’s experience, this simulates it. It’s about as stimulating as it might be to distribute fliers, or to beg for money, day after day.

Iveković is a convenient choice for a United States museum exhibition, as we’re well-primed to appreciate reappropriated magazine ads, large-scale self portraits, and the aesthetic of documentation. The territory is already limited, as feminism has inevitably been framed in the same master narrative that is the foundation of modern museums: a lax checklist cites Kruger and Holzer for advertising, Wilke, Wilson, Piper, and Mendieta for self-portraiture, Hesse, Benglis, and Bourgeois for sculpture, Abramović for masochism, et cetera. But sub Iveković for “human rights,” and that undermines the foundation of her political– and pointedly functional– work. This raises the question: is it Art?

Iveković maintains a self-awareness that has usually dried up by the advent of a major museum retrospective. She was recently quoted in MoMA’s atrium: “It is not a genius that is making art but the collaboration of many people.” The location feels contradictory in more ways than one, and throughout, that is Iveković’s most valuable asset.

{ 4 comments }

I don’t think Women’s House is referring to fashion; each of the photographs shows a large pair of sunglasses, the kind that might hide a black eye, etc.

I think they’re eluding to black eyes or masked emotion, but they’re taken from ads. Â It’s covered up in the photo here, but each includes a brand name for a high-end designer (Calvin Klein, Dolce & Gabanna, Hugo Boss, etc)

“the school of Barbara Kruger, Martha Wilson, and Hannah Wilke”?? not all of these artists are of the same generation, let alone a “school.”

I thought it was pretty clear that Wilke, Kruger, and Wilson were thrown together as “Western feminist conceptual art” rather than as a particular movement. Maybe that got lost.Â

Wilke, Kruger, Wilson, and Ivekovic were born in 1940, 1945, 1947, and 1949, respectively. They’re of the same generation.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }